To forecast our future, we have to identify patterns of change early. But rather than only seeking out collections of signals representing growth, it behooves us to simultaneously study what’s crumbling – signals of decay.

After all, growth stems from deep fractures.

One of today’s most glaring fractures worthy of our attention is higher education. The changing landscape of higher education is ground zero for radical social change and required innovation.

Good news!

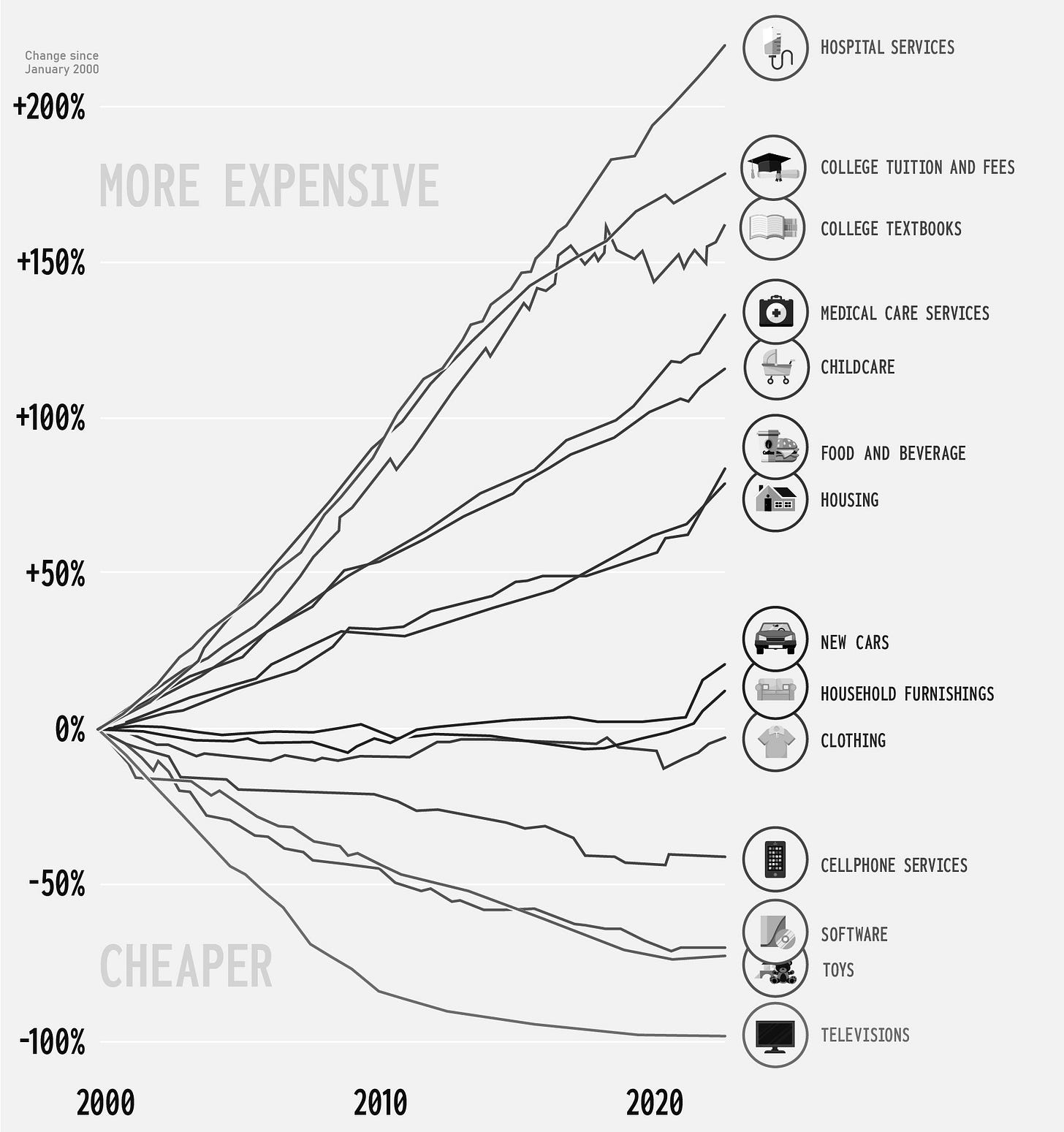

TVs, toys and software have never been cheaper in human history.

Bad news: College tuition and textbooks have never been more expensive.

This is according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics which has been tracking the prices of consumer goods and services relative to inflation for the last two decades.

College tuition — second to healthcare — is the most “increasingly expensive” buy in America.

How coincidental that these are two of the most important purchases one can obtain, and certainly the sort which more should have access to, not less?

According to the National Center for Education Statistics, in the 1968 academic year, it cost $1,545 to attend a public, four-year institution (including tuition, fees, room and board).

In 2020, it was $29,033.

For the fifth of college students attending private schools, that figure is significantly higher.

Noteworthy as the cost of (manufacturing) education and textbooks have not risen at the same rate.

Is it any more expensive to “produce” education today?

This is perhaps why NYU, among many schools across the country, are developing “Schools for Professional Studies” — certificate program alternatives dedicated to furthering education during a moment when traditional degrees are slipping.

According to a report from the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center, the number of students who earned undergraduate degrees fell by -1.6% in 2022, reversing nearly a decade of steady growth.

As of last year, only 51% of Gen Z are interested in pursuing a four-year degree, down from 71% a couple years earlier. The pandemic and Zoom screens have put things into focus. And students’ parents are on the same page: nearly half of parents don’t want their kids to go straight to a four-year college.

Graduate degrees are falling out of favor just as dramatically.

For The Wall Street Journal, Lindsay Ellis reports,

“At Harvard, widely regarded as the nation’s top business school, M.B.A. applications fell by more than 15% [in 2022]. The Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania recorded more than a 13% drop. At other elite U.S. programs — including Yale University’s School of Management, as well as the business schools at the University of Chicago and New York University — applications dropped by 10% or more for the class of 2024. Cost was the biggest factor blunting demand.”

Meanwhile, this decline is about to worsen — not just because of prices and attitudes, but because of significant demographic change.

Kevin Carey, VP for Education Policy at New America, a think-tank, wrote for Vox:

“[In 2026] the number of students graduating from high schools across the country will begin a sudden and precipitous decline, due to a rolling demographic aftershock of the Great Recession. Traumatized by uncertainty and unemployment, people decided to stop having kids during that period.

But even as we climbed out of the recession, the birth rate kept dropping, and we are now starting to see the consequences on campuses everywhere. Classes will shrink, year after year, for most of the next two decades. People in the higher education industry call it ‘the enrollment cliff.’”

Like any business facing disruption, many are pivoting to diversify revenue.

Earlier this year I learned NYU was growing its Marketing certificate program for those seeking to enter the field or gain more experiences from practicing experts. I raised my hand and began the process to volunteer as an Adjunct Professor at night.

I reviewed syllabi, audited classes, and had planning talks which spanned months. The paperwork finally began and I was set to lead seminar discussions for NYU’s Fundamentals of Advertising course.

That was until the provost learned I, myself, didn’t hold a Masters degree.

I was axed.

Despite my desperate pleas, they “weren’t interested in having any further discussions with me.”

The very institution struggling to keep up with the evolving education landscape by providing degree alternatives, couldn’t fathom that anyone without a postgrad degree could be qualified to provide their students value.

Or they did until they learned I wasn’t their ilk.

It was flawed logic academics would have loved to call out.

As a practitioner with a decade of marketing strategy experience and current guest speaker at schools including Yale, Parsons, Queens College, Franklin & Marshall, University of Oregon, and oh, NYU already that month, my lack of formal degree called for immediate disqualification.

Meanwhile, NYU’s certificate program was left with a gentleman deconstructing TV ads from the 90s to a dozen black Zoom screens. (Mind you: TV is the fastest declining advertising medium in this field's history, and this instructor’s “acceptable” higher education was a law degree.)

Am I still salty? Isn’t it clear?

It was utterly perplexing and hard not to take personally.

But then: clarity.

In a moment when higher education must be reworked and reimagined, perhaps institutions themselves may not be the best qualified providers for our required alternatives.

There’s inherent conflict and rigidity preventing these educational gatekeepers from offering a fair and valuable alternative.

As much as they want to bet on red — alternatives — they must simultaneously bet on black — protecting their historic brands and upholding the value of the traditional degree.

This may be an incompatible strategy.

This is not about me and my opportunity to teach, but about students’ return on investment, experiences and preparedness.

A genuine commitment to education would mean an integration of more diverse perspectives, and valuing practitioners’ experiences over their (lack of) degrees. Failure to prioritize students’ outcomes will only accelerate the exact reason why NYU has to develop an alternative in the first place.

NYU isn’t incentivized by its Continued Learning cohorts. It’s incentivized by its astronomically priced degrees and brand.

I was deemed a valuable asset for students until the institution learned I was at the same “academic achievement tier” as their students. My overwhelming passion, practical expertise and ultimately the students’ education were all overlooked, deprioritized.

As Clay Shirky, (coincidently, Vice Provost at NYU), put it in Bryan Alexander’s book Academia Next: The Futures of Higher Education,

“The biggest threat those of us working in colleges and universities face isn’t video lectures or online tests. It’s the fact that we live in institutions perfectly adapted to an environment that no longer exists.”

Alexander, a futurist and senior scholar at Georgetown University, wrote,

“Much of American higher education now faces a stark choice: commit to experimental adaptation and institutional transformation, often at serious human and financial costs, or face a painful decline into an unwelcoming century.”

And lastly, as Anthropologist Grant McCracken puts it,

“The university that cannot fix itself is disqualified from educating our young.”

The Value of Edu

To envision solutions for higher education and continued learning, we have to understand the current landscape and how we got here.

Understanding begets autonomy and action.

Institutional higher education is headed straight off a cliff.

If we agree not everyone has to or should get a four-year-degree from a university, why is this institutional implosion problematic?

Environments for emotional and intellectual growth are critical for both culture and society. For individual and collective growth, we should be fighting to ensure increased opportunities for people to explore new subjects, broaden worldviews, and develop critical thinking skills. This ultimately leads to increased curiosity, creativity and innovation — attributes which develop more informed and engaged citizens in our democracy.

This isn’t happening.

The inverse is — less young adults are obtaining such experiences.

The recent ruling on affirmative action will further widen the access gap to educational opportunity. How will colleges, employers, and organizations maintain their commitment to diversity and inclusion? Considerations might include new selection criteria for systems of admission, rigorous outreach programs for increasing the number of minority applicants, and stronger partnerships between high schools and postsecondary institutions with an emphasis on matriculating students who face adversity.

This decision can’t be the final word, according to President Joe Biden. He’s right. Without affirmative action, universities will be limited in their ability to consider race, ethnicity, nationality and socioeconomic status in the admission process. But that doesn’t prevent them from iterating upon decades worth of progress in diversifying America’s campuses.

We can no longer rely upon institutions to be the sole providers of continued education in our futures.

Financially, it no longer makes sense.

Approximately 44M Americans have student loan debt, amounting to more than $1.6T by the end of last year — roughly the GDP of the state of New York or the entirety of the country Spain.

While Federal Reserve data reveals adults under 30 are more likely to have student loan debt compared to older adults, nearly a quarter of outstanding student loan debt is owed by Americans over 50. This multi-generational burden restricts social mobility and cultural participation. Debt prohibits.

Meanwhile, the Supreme Court blocked Biden’s plan to forgive $430B in student loan debt. A for effort.

Is the price of education even worth it?

According to the College Board,

“In 2021, full-time workers 25 and older with a bachelor’s degree out-earned those with a high school diploma and no degree by about $27,000/yr.

But over half of grads from public four-year institutions left with federal debt averaging over $21,000.”

When many students’ main motivation for attending college is to increase their earning potential, learning that they may just break even changes things.

ROI (return on investment) also gets complicated when you take a deeper look into cost vs. earning potential...

Per The College Payoff report from Georgetown University’s Center on Education and the Workforce:

“31% of workers with no more than a high school diploma earn more than half of workers with an associate’s degree.

Likewise, 28% of workers with an associate’s degree earn more than half of workers with a bachelor’s degree, and 36% of workers with a bachelor’s degree earn more than half of workers with a master’s degree.”

Simply put, even when ignoring debt, higher education does not guarantee higher earnings. It helps. But broad stroke averages of degree-holders’ earnings obfuscate the reality:

Millions of people with lower levels of education are making more than those with higher levels of education.

Perhaps for this reason, 56% of respondents to a recent survey said a four-year degree was a “bad bet.”

For some real gut-wrenching numbers...

Melissa Korn and Andrea Fuller write in their Wall Street Journal piece Financially Hobbled for Life: The Elite Master’s Degrees That Don’t Pay Off,

“Recent film program graduates of Columbia University who took out federal student loans had a median debt of $181,000. Yet two years after earning their master’s degrees, half of the borrowers were making less than $30,000 a year.

At New York University, graduates with a master’s degree in publishing borrowed a median $116,000 and had an annual median income of $42,000 two years after the program.

At Northwestern University, half of those who earned degrees in speech-language pathology borrowed $148,000 or more, and the graduates had a median income of $60,000 two years later.

Graduates of the University of Southern California’s marriage and family counseling program borrowed a median $124,000 and half earned $50,000 or less over the same period.”

They conclude,

“Highly selective universities have benefited from free-flowing federal loan money, and with demand for spots far exceeding supply, the schools have been able to raise tuition largely unchecked.

The power of legacy branding lets prestigious universities say, in effect, that their degrees are worth whatever they charge.”

When the government guarantees loans, institutions can make the price whatever they want. As lawyer and writer Paul Skallas puts it,

“It’s a subsidy without any type of price regulation.”

Buyer beware.

In a recent report from the GAO (U.S. Government Accountability Office),

"91% of schools don’t properly list their net price, or the amount a student is expected to pay for tuition, fees, room, board and other expenses after taking into account scholarships and grants.”

The fine print is hidden. And to be clear, this isn’t just a U.S. problem.

It’s perhaps why 41% of U.K. students have considered leaving their courses due to money issues, and 68% are unable to afford course materials.

For decades, tens of millions of young adults have mindlessly enrolled in institutions under the presumption they must in order to 1. become employed and 2. earn more.

Only now, the financial repercussions and ROI cannot be ignored.

How’d this get so out of hand?

A Reversal of Figure & Ground

Oh, rankings.

The college and university leaderboards are the culprit of the current race to the top.

In business, a “race to the bottom” is a strategy where product price or service quality is lowered (i.e. sacrificed) in order to obtain more customers, market share or otherwise gain a competitive edge. Think: Amazon selling cheaper and cheaper products (even at a significant loss) in order to get more shoppers to habitually use its platform.

In education’s case, institutions have entered a “race to the top,” a strategy to rank higher and higher in order to gain their competitive edge. But here, education is sacrificed while ranking requirements and therefore position becomes prioritized.

Ranks have become a heuristic shortcut to determine the quality of education and therefore job preparedness... which then means organizational value, and therefore earning potential.

It’s flawed.

Yet for both institutions and students it’s hard to think otherwise. We’re missing the big picture.

Rooted in Gestalt psychology, this larger phenomena is called “a reversal of the figure and ground” — whereby the original purpose of something (ex. education quality) becomes eclipsed by a once secondary element (ex. alumni giving). Today, the latter has become more important than the former.

Media theorist Douglas Rushkoff explains the original reversal of the figure and ground in education in his book Team Human,

“Public schools were originally conceived as a way of improving the quality of life for workers.

Teaching people to read and write had nothing to do with making them better coal miners or farmers; the goal was to expose the less privileged classes to the great works of art, literature, and religion.

A good education was also a requirement for a functioning democracy. If the people don’t have the capacity to make informed choices, then democracy might easily descend into tyranny.

Over time, as tax dollars grew scarce and competition between nations fierce, schools became obliged to prove their value more concretely. For the poor in particular, school became the ticket to class mobility. Completing a high school or college education opens employment opportunities that would be closed otherwise.

But once we see competitive advantage and employment opportunity as the primary purposes of education rather than its ancillary benefits, something strange begins to happen.

Entire curriculums are rewritten to teach the skills that students will need in the workplace. Schools consult corporations to find out what will make students more valuable to them. For their part, the corporations get to externalize the costs of employee training to the public school system, while the schools, in turn, surrender their mission of expanding the horizons of the working class to the more immediate purpose of job readiness.

Instead of compensating for the utilitarian quality of workers’ lives, education becomes an extension of it. Where learning was the purpose — the figure — in the original model of public education, now it is the ground, or merely the means through which workers are prepared for their jobs.”

The figure and the ground has reversed around education and brand.

Ranking, or brand name, is now in the driver’s seat, optimistically determining employment and earnings. Life preparation and measurable ROI are now moot, left in the dust.

For those who decided (or still decide) to enroll, really, it’s the paper degree, network and ranked logo which matter most.

As NYU professor and marketer Scott Galloway puts it,

“The ultimate luxury brands in the world are now American universities.”

Higher ed’s sold product is now just the brand itself.

It’s gone meta.

We’ve lost the plot.

Colin Diver, a former college president, university dean and author of Breaking Ranks: How the Rankings Industry Rules Higher Education and What to Do about It, reminds us,

“Every step in the [ranking] process — from the selection of variables, the weights assigned to them and the methods for measuring them — is based on essentially arbitrary judgments.

U.S. News, for example, selects 17 metrics for its formula from among hundreds of available choices.

Why does it use, say, students’ SAT scores, but not their high school GPAs? Faculty salaries but not faculty teaching quality? Alumni giving, but not alumni earnings? Why does it not include items such as a school’s spending on financial aid or its racial and ethnic diversity?

Lurking behind data manipulation lies the even larger problem of schools altering their academic practices in a desperate attempt to gain ranking points.”

As the consultancy McKinsey rightly points out, institutions focusing on the same criteria lead to greater homogenization, while we should instead be focusing on more distinctiveness.

All institutions attempt to emulate the elite.

Today, institutional spending on student services (food, gyms, events, stadiums, etc.) is now growing 4x as fast as instruction.

But for institutions, deciding to roll back these amenities doesn’t mean others will too... they’ll now just be the weaker choice.

With all due respect, the ways in which young adults with not yet fully developed brains are told that these luxuries are somehow related to their education, and further, are encouraged to see college ranking as synonymous with their personal worth is unnecessarily anxiety-provoking, maliciously deceptive and borderline fraudulent.

So as it all falls apart, what can we do?

There’s two ways to approach our moment:

We’re likely too far gone to revert back to our original figure and ground. If higher ed is now the means to secure employment and social capital, institutions must do a better job at adapting to this reality.

But second, this is not to say the ethos of exploration and personal development cannot remain embedded within institutional programs, or that these two approaches can not co-exist.

They can.

The future of education requires a “yes and” mentality: theory and practice.

Changes & Solutions Spaces

Institutional higher education is in free fall, its future is unwritten. As tuition rises, enrollment drops, and confidence in institutions continues to decline, institutions simultaneously face new conditions, namely the growing demands of employers, the new expectations of learners, and the forceful cross-winds of technology and inequality.

Prioritizing the student, we see five unique spaces where unprecedented change will manifest, and that’s where our attention is required.

01. Re-evaluate Employment Qualifications

With all that’s been discussed, there’s rightfully been a loosening of degree requirements, permitting more diverse and equally qualified — and sometimes more qualified — talent to enter the workforce.

Between 2017 and 2019, employers loosened degree requirements for 46% of middle-skill occupations and 31% of high-skill ones. We should expect these numbers to rise. Good.

While Maryland, Pennsylvania, Utah, and Alaska will no longer require four-year degrees for thousands of state jobs, Obama and Biden are continuing to encourage more companies to strip their degree requirements in what’s being dubbed the ”Paper Ceiling” and “Diploma Divide.”

College shouldn’t be the only pathway for prosperity. Full stop.

This top-down normalization will be incredibly effective at changing the culture, lessening the pressure of taking on debt and encouraging the pursuit of education outside the institution.

According to Kate Naranjo, an Economic Mobility Policy Advocate and Non-Profit Strategist,

“If we want to rebuild economic mobility, we must see both college and alternative routes as viable ways to build a thriving labor force and a path to the middle class. [...] We already know college alone cannot fix declining economic mobility because it does not pay off equally for all workers.”

To redefine how we label someone as “qualified” — beyond merely eliminating degree requirements — we must also accelerate skills-based hiring allowing the over 70 million workers over the age of 25 who are “skilled through alternative routes” (i.e. STARs) a chance to compete for jobs for which they are trained in. These skill-based trainings are a sound investment and an opportunity for partnership and experimentation.

As interest in degrees slip, it only makes sense to deprioritize credentialism and disempower the chokehold that elite institutions and college rankings have on society’s understanding of merit.

But for as long as we still see college tethered to employment, we have to address institutions’ (evolving) role regarding qualifications — their online certification programs and classes are just a start.

Part of this onus explicitly falls on career services. Less emphasis should be placed on basic job information and more on equipping students with robust professional networks and forming partnerships with employers which lead to good-paying jobs in graduates’ field of study.

For example, the University of Tennessee announced the Tombras School of Advertising and Public Relations in partnership with Tombras, a Knoxville-based ad agency. According to the vision, students will be taught in classrooms which resemble spaces in the industry, and curricula will be continuously enriched by insights from Tombras. This way, coursework will stay relevant and useful as a result of the direct feedback and communication between college and employer – a dynamic which is scarce. This will also effectively increase the advertising industry’s diverse representation, confronting the “talent shortage” often expressed by employers.

Inarguably, courses taught with Tombras will develop better prepared employees.

But why enroll in the University of Tennessee to receive an education from Tombras, if one could just receive a Tombras education (and then Tombras job) without the University of Tennessee as a middle-man and its ludicrous tuition? How can this happen?

While evolving requirements and partnerships to address employment are needed, they don’t wholly rectify the problem of access and quality of the education itself.

02. New Environments & Teachers

In “Future 2043,” a report by innovation consultancy SpringWise forecasts:

“School will likely be a concept rather than a place where our children go to learn.”

When “education” is reduced to information — we recognize how absurd the price tag of institutions has become. Remember: the university model was concocted before the internet. Never before in history have students had this much access to the world’s best material (books, lectures, videos, experts, interviews, galleries, etc.) — much of which is currently free.

It’s like continuing to ask people to pay for individual songs via iTunes when the norm is free, ad-sponsored or unlimited music for just a small fee. But instead of $9.99/mo., it’s $2,132/hr.

The value of education is not just the information, but the environment in which it’s learned in — more precisely, the physical or virtual spaces, and those who inhabit them: teachers and students.

MOOCs (massive open online courses) have had some traction — Coursera, an online education platform, alone has reported +100M users, 7,000 courses and found 87% of students reported career benefits like a new job or promotion.

But what you gain in scale you lose in that valuable component: environment.

As a result, one study found that only 3% of MOOC participants finish a course.

Environment is absolutely critical when education becomes an online video.

There must be something in between a free MOOC and an exclusive, pricey university campus.

What does this look like? That’s for us to decide.

Whatever it is though, it allows us to address various learning preferences, become more flexible in every respect, and integrate countless forms of diversity – particularly age if we want a future of lifelong learners.

It's an immeasurable opportunity... and brands are perfectly poised to substitute teach. This is a real opportunity for brands which fight everyday to position themselves as trustworthy experts and have existing cultural and financial capital.

What is the professorial role of a brand in a future where there are no walls to a classroom?

Imagine: Agriculture & Logistics brought to you by Sweetgreen, Physiology by the NBA x Alo, Network Dynamics by Verizon, or Intro to Film & Animation by Disney. It’s not that ludicrous. Toyota already has a technical training program in partnership with vocational schools, McDonalds offers a leadership and management degree at Hamburger University, and Grow with Google is now teaching countless courses including CyberSecurity.

But again, the environment is key. We can’t forget that. A video and chat room won’t cut it here. But you don’t need a campus or football stadium either.

Wherever or whoever is teaching, intimacy, accountability and community is what must be woven in. The latter, community, is perhaps the most important. After all, “network” remains one of the most attractive selling-points of institutions today. When envisioning our alternatives, who is within these environments and what are the opportunities for them to connect, collaborate and benefit from one another?

Meanwhile, there’s also the bottom-up approach to these new environments and teachers — DAOs (Decentralized Autonomous Organizations) notwithstanding.

There are now countless platforms for allowing anyone to teach — for better or worse. There’s Podia, Teachable, Kajabi, Thinkific, Memberful, Loom, Circle, Studio, Course Studio and Maven for starters.

Imagine an immersive Masterclass for the Long Tail.

A couple of years ago Emily Gillcrist founded Vital Thought, a human-centered education and consulting platform, which allows PhD experts to teach intimate cohorts, monetizing their experiences, and also allows the general public to receive invaluable insight.

Courses range from “Games and Gods” and “Earth Systems Theory,” to “Ethics of the Dead: Remains in Museums” and “Science & The Occult.”

Gillcrist shares,

“In order to really democratize education we need to invest not only in the distribution and access to information and content, but we need to support teaching and environments where learning can be cultivated over significant periods of time.

Education is not simply a download.

I believe that living human beings are the arbiters of knowledge and value, they are the ones who can develop the expertise to interpret the meaning and value of the hordes of complex and often contradictory information being relentlessly collected in every corner of society.

That ability to interpret is indispensable right now.

I am aiming to cultivate spaces that function as contexts of meaning, so experts can share their insight with people who want to listen and learn while sharing and enriching their own views and those of everyone in their cohort.”

In 2006, the movie Accepted premiered, a comedy about mis-fit high school graduates who build a fictitious college to get their parents off their backs. They call it The South Harmon Institute of Technology or S.H.I.T. But in the end, they learn to co-teach one another in exotic yet exciting and practical courses. The cornucopia of passionate learning pods, buck the status quo, reject conformity and kindle their own special environment. At the film’s rising action, Justin Long pleads with the established university that’s trying to shut down S.H.I.T.,

“Why can’t we both exist?”

In Accepted, the ultimate draw for students was the ability to co-author their curriculum. They studied what they wanted.

2-in-5 American college graduates regret their major. For those with humanities and arts degrees, that number is nearly half.

But there’s a reason behind why these students originally select these subjects in the first place: curiosity.

Our solution isn’t to sway students into fields where they feel their degree is ultimately worthwhile.

Perhaps it’s finding the practicality of their interests, explicitly connecting it to employment preparedness, and also offering opportunities to explore interests for exploration sake.

We can decouple employment preparedness and intellectual curiosity, offering solutions for students simultaneously. These offers don’t even have to come from the same education provider.

Call it: Holistic Education.

03. HEAL ≥ STEM

...But for those who see higher ed’s sole purpose as the gateway for a related career, we need preparedness for jobs not only in STEM but also in what Senior Fellow at the Brookings Institution Richard Reeves calls “HEAL” jobs (Health, Education, Administration, and Literacy). This is particularly critical for men.

In Reeves’ book, Of Boys and Men, he shares,

“In 1980, women accounted for just 13% of jobs in the STEM field (Science, Technology, Engineering and Math); the share has now more than doubled, to 27%. But the same is not true in the other direction. Traditionally female occupations, especially in what I call the HEAL fields have, if anything, become even more ‘pink collar.’

Just 26% of HEAL jobs are held by men, down from 35% in 1980. The gender desegregation of the labor market has so far been almost entirely one-way.

While women are doing ‘men’s jobs,’ men are not doing ‘women’s jobs.’”

It is imperative not to prioritize career fields within STEM over careers in HEAL.

Each field serves a unique purpose within society and must be presented objectively as an option for consideration, despite any stereotypes associated with each.

According to Reeves, the main reasons why we need more men in HEAL is to 1. address the decline in traditionally male occupations, 2. provide a better service to boys and men, and 3. help meet labor shortages in critical occupations like nursing and teaching.

If women belong in STEM, then men belong in HEAL.

This is certainly true from a moral standpoint. But it is also pragmatic when thinking about one way to address the absolutely staggering humanities crisis within universities.

Take psychology, for example:

“The proportion of men in psychology has dropped from 39% to 29% in the last decade. Among psychologists aged 30 or less, the male share is just 5%.”

This gender imbalance establishes a false perception that only women are best suited to be psychologists when, in fact, the occupation demands perspectives and representation from all genders.

And this doesn’t just apply to psychology. The share of male teachers is incredibly low where men account for just 24% of K-12 teachers, down from 33% in the early 1980s.

“Only one in ten elementary school teachers are male. In early education, men are virtually invisible. It ought to be a source of national shame that only 3% of pre-K and kindergarten teachers are men.”

Humanities enrollment has plummeted in recent decades due to women flocking to STEM and men avoiding HEAL — often guided by the notion that a STEM degree enhances their job prospects and income potential, which is understandable (but not an absolute truth).

With this, we need to change the narrative surrounding HEAL like we’ve managed to do with STEM so that every student feels encouraged, not forced, to pursue an occupation in this field, so long as it’s actually an interest.

04. With, Not Against AI

While we work on laxing demands around degrees, and envision alternatives, we must also address (and call on) the elephant in the room — AI.

Artificially intelligent text generators (AITGs) like ChatGPT are already disrupting classrooms.

Students are using these tools to complete assignments, and immediately, educators are voicing concerns around students’ over-reliance on them. (Not to mention the debates around whether or not the college essay is dead or alive, further questioning qualifications.)

In fact, the first year of college with the introduction of AI ended in “catastrophe,” according to professor Ian Bogost and writer with The Atlantic.

He forecasts how this tech will continue challenging the traditional dynamics of higher ed institutions:

“One way or another, the arms race will continue. Students will be tempted to use AI too much, and universities will try to stop them. Professors can choose to accept some forms of AI-enabled work and outlaw others, but their choices will be shaped by the software that they’re given. Technology itself will be more powerful than official policy or deep reflection. Universities, too, will struggle to adapt. Most theories of academic integrity rely on crediting people for their work, not machines. That means old-fashioned honor codes will receive some modest updates, and the panels that investigate suspected cheaters will have to reckon with the mysteries of novel AI-detection ‘evidence.’ And then everything will change again. By the time each new system has been put in place, both technology and the customs for its use could well have shifted.”

If college campuses plan to persist into the future, and if we are to develop higher ed alternatives, all must accept the responsibility of reevaluating how they perceive, address, and work with technology.

Academia should neither view technology as a threat to learning nor a tool for cheating, but rather, an opportunity to teach students how to be honest and adaptable in an evolving society, and further as a scalable, intellectual sparring partner.

Rather than wait or avoid the inevitable, IE University in Madrid, Spain already dove in, actively reinventing higher education by welcoming AI into the classroom as an essential part of the future of higher education and a valuable addition to the pursuit of scholarship.

But with all of these possibilities comes two stark reminders:

First, ask ChatGPT to answer, “What weighs more? Five pounds of feathers or one pound of bricks?” And it will answer, “The bricks.” That’s because the AI is not actually intelligent as much as it is exceptional at guessing which word should come next in its answer. There is no real logic here. So if we’re to throw these tools in the classroom, and increasingly rely upon them in “the future of work,” it suits us to strengthen our own logic, reasoning and critical thinking.

And second, the desire to engage with these technologies may reveal a deeper rooted issue.

Instead of banning students from using these tools, we should question why they’re so attracted to them in the first place.

How do we engender environments where students feel empowered to choose topics they are genuinely interested in, rather than mandate curriculum and assignments which lead them to cut corners, only learning how to use ChatGPT to accomplish tasks?

And lastly in regards to employment, with headlines projecting the dire displacement of humans to AI in the workforce, we must remember our own hand in this: AI does not displace humans, humans displace themselves with AI. We get to, and should, mindfully orchestrate our collaboration which benefits us, not the machine.

05. Growth & Identity

As we interrogate and reinvent education itself, we’d be mistaken not to address another value prop of the institution. When the traditional college experience is no more, how do we kindle alternatives for social experiences and rights of passage?

We need to find new ways for people to grow emotionally and find worth beyond school rankings.

Ian Bogost puts it bluntly,

“Without the college experience, a college education alone seems insufficient. Quietly, higher education was always an excuse to justify the college lifestyle. But the pandemic has revealed that university life is far more embedded in the American idea than anyone thought. [America is] far less interested in the education for which students supposedly attend. In the United States, higher education offers a fantasy for how kids should grow up: by competing for admission to a rarefied place, which erects a safe cocoon that facilitates debauchery and self-discovery, out of which an adult emerges. The process — not just the result, a degree — offers access to opportunity, camaraderie, and even matrimony.”

But while colleges like to promote themselves as the destination where students go to revel in their newfound independence as young adults, what consistently takes place on university campuses, in many ways, does not resemble the nuanced realities of adulthood — nor does the four-year program fully educate graduates on how to engage with the real world or participate in its workforce.

Who says the campus was the best method for growth?

As we innovate across the board, we must examine emotional growth as much as we are concerned with intellectual growth.

The School of Life is a shining example of an organization outside the institution engendering emotional growth through books, articles, games, events, videos, and counseling services. Ranging from self knowledge, relationships, and sociability, to work, calmness and leisure, The School of Life media platform is teaching the invaluable skills which must be a part of our education reform conversations.

But we have to address more than just growth. College (and their rankings) provide a profound sense of identity, pride and self-worth — although also suspect.

Author William Deresiewicz believes,

“[A]n elite education inculcates a false sense of self-worth. Getting to an elite college, being at an elite college, and going on from an elite college — all involve numerical rankings: SAT, GPA, GRE. You learn to think of yourself in terms of those numbers. They come to signify not only your fate, but your identity; not only your identity, but your value. It’s been said that what those tests really measure is your ability to take tests, but even if they measure something real, it is only a small slice of the real.”

Where else may this self-worth come from? And further, can we craft environments for experimentation and failure, rather than performance and perfection?

He concludes,

“If you’re afraid to fail, you’re afraid to take risks, the most damning disadvantage of an elite education. It is profoundly anti-intellectual. [...] The system forgot to teach [students], along the way to the prestige admissions and the lucrative jobs, that the most important achievements can’t be measured by a letter or a number or a name.

It forgot that the true purpose of education is to make minds, not careers.”

At this radical moment of change, we have the opportunity to reshape what we want from higher education... and we all have a role — makers, marketers, investors and thinkers alike. We get to author what comes to replace institutions as we know them.

And while doing so, we should remember the moment before the figure and ground reversed: when education wasn’t for logos on LinkedIn, but for whatever made more fulfilled and engaged citizens.

There’s a blank page in front us.

Time to start drafting.

A deep, heartfelt thanks to Robert Cain for the invaluable research, drafting and edit support in this piece.