Originally published via Future Commerce

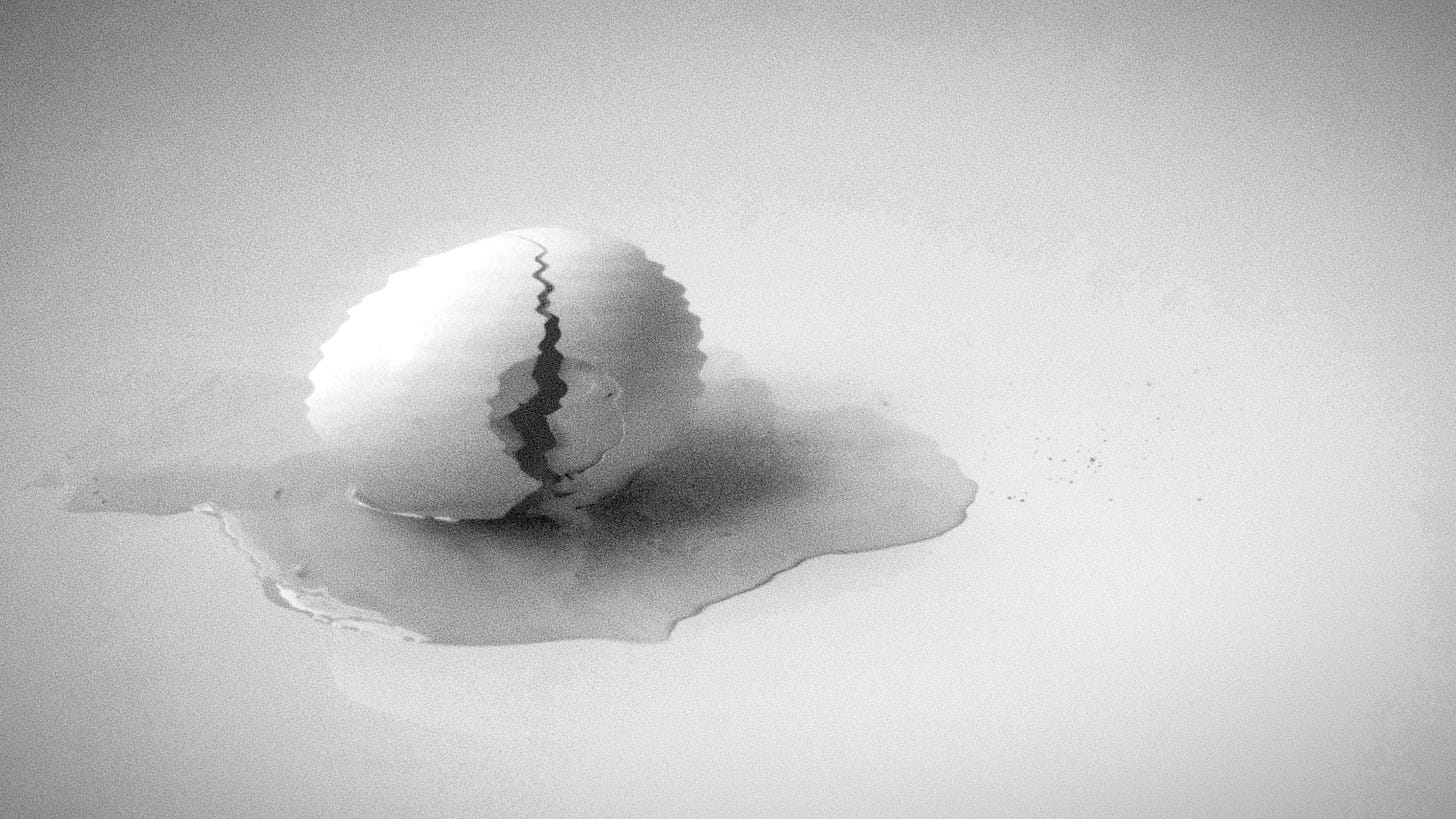

Have you heard of the infamous “Betty Crocker Egg” story?

It goes:

During the 1950’s, sales of instant cake mixes were struggling. A worried General Mills, owner of the Betty Crocker brand, brought in consumer psychologist Ernest Dichter (creator of the focus group) to conduct interviews with housewives.

In his discussions, he learned that housewives’ guilt from the effortlessness of the instant cake mix made using the product “too simple.” The process (or lack thereof) was self-indulgent “cheating” compared to the more rewarding process of baking from scratch. Therefore, the mix was a problematic buy.

An insight and opportunity: “What if we left out the powdered eggs from the mix and allowed people to add fresh ones themselves, increasing participation, decreasing guilt, and ultimately increasing sales?”

It worked. Once the new cake mix requiring fresh eggs was released, sales of the product began to soar — a win for both the baker and brand.

This story reveals the seemingly irrational consumer mind and is a case study of the importance of in-person qualitative research. Only by looking beyond market data could we learn about “premium friction” or that the opposite of a good idea (e.g., more work, not less) may also be a good idea. For this reason, marketers, strategists and innovators alike love sharing it.

The Betty Crocker tale supports “The IKEA Effect,” a cognitive bias coined by behavioral economist and author Dan Ariely. As proposed in his study, by putting together our furniture (rather than buying it pre-assembled), we create a unique, more personal relationship with it, increasing the perceived value of our creation. Like requiring fresh eggs, our participation changes perceived value.

But here’s the problem:

The “Egg Story” as we know it is bullshit.

Critical Omissions and Confirmation Bias

Why is it bullshit? It’s missing critical nuance.

There are five missing details which re-tellers leave out:

First, Dichter’s findings include, but no one acknowledges, that fresh eggs produce superior cakes.

Author and historian Laura Shapiro confirms this overlooked truth in Something from the Oven: Reinventing Dinner in 1950s America:

"Chances are, if adding eggs persuaded some women to overcome their aversion to cake mixes, it was at least partly because fresh eggs made better cakes."

The original dry egg mix produced cakes that stuck to the pan, burnt quickly, had a shorter shelf life, and tasted like eggs. We knew fresh eggs made for better cakes because...

Second, a patent for fresh eggs in cake mixes was first filed in 1933, decades before Dichter discovered their “psychological importance.” The original patent reads:

“The housewife and the purchasing public in general seem to prefer fresh eggs...”

Companies were debating dry vs. fresh eggs since the very inception of the cake mix product, not just when “sales were struggling.” (More on that in a second.)

Paul Gerot, CEO of Pillsbury during the time called the egg mix “The hottest controversy we had over the product” from the get-go. The story makes it seem like fresh eggs were this novel discovery. In reality, these companies had been debating them for years.

Third, around this time, cake mixes were actually selling incredibly well, but only when they weren’t flying off of shelves did it cause worry.

Between 1947 and 1953, sales of cake mixes doubled. The concern only arose during the late ‘50s, when there wasn’t a “decline,” but just a modest +5% growth — a “flattening,” if anything.

Cake mix sales didn’t suddenly flatten at once because of a mass onset of guilt... especially after years of excitement and growth. There are endless explanations for a flattening such as novelty wearing off, market saturation, product competition or evolving tastes.

The story makes this seem like a brand problem when in fact it was a shared category problem. Which brings us to...

Fourth, when sales stalled for the category, General Mills and Pillsbury adopted two different strategies:

General Mills required the fresh egg, while Pillsbury offered the complete dry egg mix.

If the fresh egg were such a business-saving idea, we should have seen Betty Crocker wipe Pillsbury out of business.

We didn’t. Pillsbury still thrives today.

And fifth, while Dichter was onto something with baker participation, the egg shouldn’t be the star of this story; it should be icing.

According to historian Laura Shapiro, it wasn’t as much the fresh eggs that brought cake mixes back from their slowed growth but inspirational advertisements empowering homemakers to decorate their cakes with extravagant and personal flair. The introduction of frosting and elaborate decorations turned excitement away from the cake's inside and taste, to the cake's exterior and splendor.

This is how General Mills and Pillsbury brought cake mix sales back to life — through the broader cultural turn towards the mimetics of homemaker aesthetics.

As Michael Park writes for Bon Appétit on the history of cake mixes:

“It didn't hurt that slathering a cake-mix cake with sugary, buttery frosting helped mask the off-putting chemical undertones that still haunted every box. It worked. By the time the over-the-top cake-decorating fad was over, cake mixes had invaded the average American kitchen, and have been there ever since.”

There we have it: the full story of Dichter and Betty Crocker’s egg.

Alternative Truths Form Their Own Realities

But with these untold truths now laid out, new lessons emerge.

First and foremost, nuance isn’t fun and doesn’t make for biting hot-take lessons on social media. Details are inconveniences and potential contradictions when pithiness spreads. It reminds us to question our viral headlines: “What’s missing?” Something always is.

When an alternative “truth” like the almighty fresh egg eclipses the real truth (the complete story of egg patents, real sales figures, and icing), new realities form. Stories don’t have to be true to be effective – they just have to sound right; or confirm our existing biases.

The world we perceive is manufactured from the stories we hear.

Any narrative which prevails becomes “the truth,” whether it’s complete or factually correct. Perception is reality and reality is only the stories available.

But aren’t all of our stories made up? Isn’t everything just a social construct?

In 2021, Dan Ariely (author of that “The IKEA Effect” paper) was accused of manipulating his data in a 2012 study after other researchers could not replicate results and considered his raw data suspiciously manipulated when compared with the published findings in the study.

The paper was later retracted.

The he-said-they-said drama thickens. While Ariely claims he didn’t touch the raw data provided to him, in a statement to NPR, The Hartford (the originator of the consumer data) insists that someone altered the data after they gave it to him.

There’s different data, but neither party supposedly altered it.

Meanwhile, Harvard Business School professor Francesca Gino, a collaborator of Ariely, is currently on leave after being accused of falsifying her data... from the same exact 2012 study that Ariely is accused of.

The kicker: this paper is about “nudges” to prevent people from lying.

Over the last decade, behavioral economics has become a thrilling topic for psychologists, marketers and all interested in the mind. Ariely puts it best as his book title — we’re Predictably Irrational. One study by Gino claims silently counting to 10 before deciding what to eat can increase the likelihood of choosing healthier food.

It’s now common to believe that small “nudges” like requiring a fresh egg can influence our psyches at scale. Further, our behavioral idiosyncrasies can be distilled down and explained by simple cognitive biases.

Or maybe not.

What if we don’t know as much as we think we do about what’s happening inside our brains. Maybe we can’t actually explain stalling cake mix sales. And maybe signing the top of a piece of paper doesn’t actually prevent lying as Ariely and Gino’s paper suggests.

Maybe we just don’t know.

And that’s okay.

Our current moment with UFOs, or now UAP’s, “unidentified anomalous phenomena” is a great exercise.

When a former Navy pilot testifies in-front of Congress that the Pentagon is hiding evidence of alien spacecrafts and knowledge of “non-human remains” we’re left with an opportunity.

The real truth here is that we’ll never ever get the full truth. We’re invited to admit, “Maybe we’ll just never know.”

Wonder, awe, mystery and unknowing are beautiful traits that our AI competition will never experience. Bask in naivety. One of our fatal flaws is our adamancy that we know how everything works. How may we be happier or more productive if we were mindful of our hubris?

On a warpath for not just truth, but an easy truth, we overlook other valuable lessons: the world cannot always make sense, personalized participation (icing) is more effective than conventional participation (eggs), and elusive focus groups may not reveal as much as some extensive desk research may.

Yes, there’s a purpose for the half-truthed Betty Crocker tale, but there’s much to be learned in full-truthed tales. We should be open to the full truth as much as we’re open to admitting we just don’t know.

And if there’s a pithy story to come from the Betty Crocker tale, it’s not about the power of participation. It’s that maybe your product is just crap.