The Art of (Attention) War

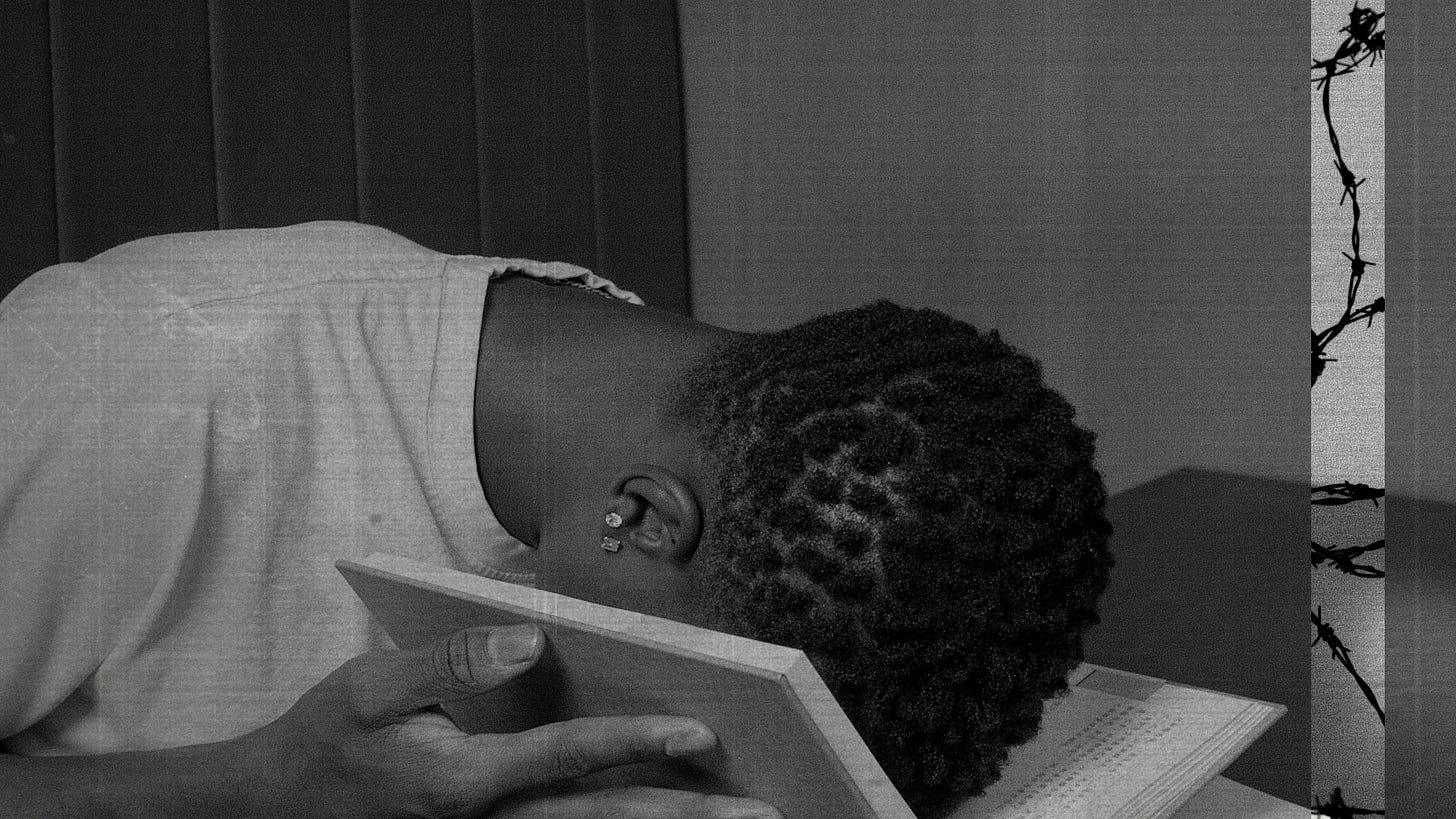

How to win back our attention as the infinite is making us insane

Preface:

In a series of essays in partnership with Squarespace, we’re making sense of our relationship with reality and how culture is constructed.

Making it real is now an act of rebellion, a middle finger to the paralysis brought on by consensus collapse. The line between fact and fantasy continues to blur, but when reality is this negotiable, the soil for preferred futures is fertile. You can just do things. What’s the future you want to see? Making reclaims agency amidst lost meaning. So, don’t escape this reality — design the one you want. We desperately need your alternatives.

Literally make anything real with -10% off any site. I’ve been using Squarespace for 15 years, and cannot recommend them enough.

A website makes it real. Design your world and then get discovered this new year. With built-in tools for SEO and visibility, ensure your vision is discoverable. Track attribution with advanced analytics to learn how or where your audience is coming from. Build a future and find your people.

The following piece is a collaboration between Matt Klein + Nick Susi.

Nick Susi is a writer and strategy executive, exploring the technological, societal and psychological forces that shape our identity, perception and culture. He has led strategy for dotdotdash, Complex, The FADER and Jay Z’s former media brand Life+Times. His research and writing can be found in Business Of Fashion, Metalabel, Dirt, Boys Club and Joshua Citarella’s Do Not Research.

ATTEN-TION!

Why are you here?

We are at war.

An attention war.

And right now, soldier, we’re losing on all fronts.

In the 5th century BCE, Chinese general and philosopher Sun Tzu wrote The Art of War. It’s the oldest known military treatise in the world. It’s a collection of numbered maxims on how to understand and win battles. Now, in our modern attention war, perhaps there are some amendments to be made to his principles for surviving a battlefield where our own minds are under siege every waking second.

And make no mistake. If you don’t learn to command your attention, soldier, someone else sure as hell will.

01.

THE PATH TO THE INFINITE IS THE PATH TO MADNESS

For thousands of years, across ancient history to modern culture, a mythic archetype continues to be repeated.

Take Odin, the one-eyed old warhorse of Norse legend. He’s often depicted with an eye patch or an empty socket. But what happened to poor old Odin’s eye? In his obsessive hunt for wisdom, he discovered Mimir’s Well, a sacred spring rumored to hold infinite knowledge. But it came at a terrible price. Odin gouged out his own eye, ripped it clean out of his skull, and tossed it into the well for a single drink. With that sip, infinite knowledge flooded into him. He traded partial blindness for a different form of perception. But even with all this knowledge, Odin was the god of war, frenzy and madness.

In 1942, Jorge Luis Borges told the story of “Funes The Memorious,” who, after a horseback riding accident, gained perfect, total, infinite memory. But what seemed like a gift quickly became a curse. Infinite information utterly overwhelmed him. He couldn’t think, speak or live normally. The infinite didn’t expand his world. It crushed him.

In 1964, X-Men introduced Cerebro, a supercomputer that connects the mind of the user to every single mutant on Earth all at once. But this is lethal to the untrained mind. It instantly invites infinite noise directly into the user’s brain, causing extreme psychic overload, even coma or death.

In every myth, the lesson is the same: The path to the infinite is the path to madness.

And yet, we still gouge out our eyes. We plug our untrained minds into the infinite machines – our smartphones, our social media, our Oura rings, our prediction markets, and our AIs. And as a result, we are going mad.

02.

THE MIND THAT ENTERS LIMITLESS TERRAIN WITH LIMITED CAPACITY INVITES DEFEAT

William James, one of the fathers of psychology, once wrote,

“Attention is the taking possession by the mind.”

So what, exactly, are we allowing to take possession of our minds?

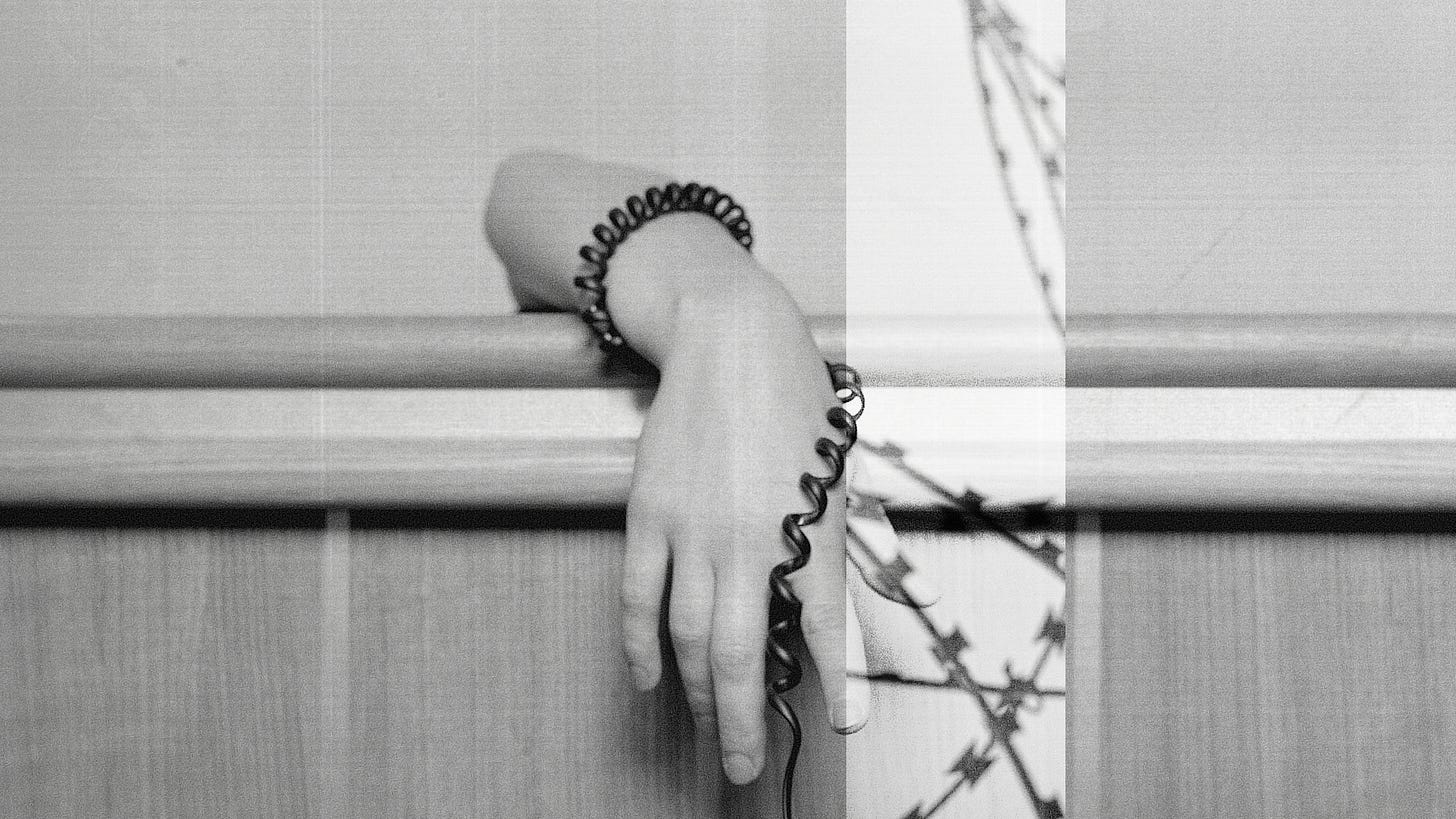

We are not built for the infinite. The human brain is powerful, but finite. And our attentional capacity is a limited resource. Nelson Cowan, a leading researcher on working memory, tells us the Magic Number is 4±1. Meaning, we can only focus our attention on three to five meaningful chunks of information before our cognitive capacity overflows. Now, how does that compare to the number of tabs you have open right now? The number of TikToks you’ve scrolled today? The number of unread emails sitting in your inbox?

When we exceed the Magic Number, we risk ego depletion. When our cognitive load becomes too high, our self-control depletes. We become a soft target – more impulsive, more predisposed to reach for short-term gratification, distractions, rage bait, junk food, gambling and buying more things we don’t actually need.

But what about paying constant attention to the things that really matter? Global crises, suffering, injustice? Isn’t it our duty to care for our brethren?

Noble, yes, but there’s a paradox here. The more suffering we try to absorb, the less we’re able to act. This is called psychic numbing. Compassion fatigue. It’s a defense mechanism where empathy and the ability to respond collapses as the scale of tragedy increases. The mind can’t metabolize the infinite, so it shuts down. This is why a single person’s story can sometimes move millions more effectively than statistics of mass suffering. Even Mother Teresa, the saint herself, has said,

“If I look at the mass I will never act. If I look at the one, I will.”

It’s not that we don’t or shouldn’t care, but because the infinite exceeds the limits of human capacity.

03.

THE FIELD OF ATTENTION IS THE FIELD OF REALITY

Our attention deserves protection, because our attention is our reality.

Remember the Invisible Gorilla Test? People watch a video of players passing a basketball and are told to count the passes. While they’re focused on counting, a person in a gorilla suit walks through the scene. Afterward, when asked, “Did you catch the gorilla?” most people never noticed it. The test reveals how easily our visual field and perception fail based on how and where we pay attention.

Attention is our field of view – the small slice of the world that our mind chooses to look at.

That field of view becomes our reality tunnel – a narrow corridor carved by what holds our focus, shaping what we notice and, equally, what we miss. That reality tunnel becomes our perceived reality – the world we believe we’re in, simply because it’s the only world we’re seeing. And our perceived reality becomes our lived action – it dictates how we move, what we choose, who we become.

We must strategically protect and take aim with our attention, not just because it’s the lens through which we see, but because it’s the architecture of our reality.

04.

KNOW THY ENEMY: A 24/7 CULTURE WITHOUT REST

How did we even get here? How did we begin to desire and attempt to pay attention to the infinite, which consistently defeats us?

Much of the current discourse would blame our collapse of attention, and with it, shared reality, on modern technologies – smartphones, social media, algorithms, AI. But the attention war began long before any of that.

Art critic Jonathan Crary’s book 24/7 explores how we entered a culture that battles against rest and time itself. A nonstop 24/7 culture that never turns off. If attention is finite, a 24/7 society fights to expand the surface area of waking time to capture more of it.

Reed Hastings has famously stated that Netflix’s main competition isn’t other media or entertainment companies. It’s sleep.

This acceleration really took off with cable news and the birth of CNN in 1980. TV news and programming stopped ending with nightly sign-offs. It stopped syncing with the rhythms of our sleep cycles. Media became an infinite loop of endless, real-time information.

There have been even stranger attempts to literally extend our daylight. In 1993, Russia’s Znamya project sent mirrored satellites into orbit to try to reflect sunlight back onto Earth to increase the time and attention available for productivity.

Our culture tempts us to strive for an aspirational identity rooted in infinite information and the illusion of potential mastery over it.

But there is no endpoint, only an ever-growing stream of content. We face a nonstop 24/7 loop of madness.

05.

THAT WHICH SEEKS ATTENTION CANNOT BE DEFEATED BY GIVING IT ATTENTION

Information expands to fill the space available, and in our 24/7 culture and modern media environment, the space available is infinite. This means there are now more news stories than there is actual news. W. David Marx calls this the Parkinson’s Law of Media.

Marx argues that ad-driven platforms financially incentivize all media – and at this point, nearly every company and person is media – to endlessly react and reproduce more media on anything that trends. The tiniest spark of a story can quickly explode into what feels like a full-blown cultural atomic bomb.

Further, Marx explains that the aspirational identity around media literacy has drifted toward a belief that we must remain fluent in every single thing online – high culture, low culture, things we love, things we hate. This traps us in an endless chase to consume every. single. narrative.

But by the time we’re arguing about whether something is real or fake, good or bad, important or meaningless, the battle is already lost. The attention war itself won, and we are the spoils.

Personalities, products, and subcultures win simply by demanding attention, even from their haters. This creates a hyperstitious loop. Debate and critique disproportionately amplify the very thing we hope to squash, pushing it further into existence and significance through repetition.

In The Art of War, Sun Tzu wrote,

“Do not swallow bait offered by the enemy.”

We cannot defeat that which seeks attention by any means necessary by giving it attention. This is the paradox at the heart of the attention war.

06.

THE DIGITAL REALM APPEARS INFINITE TO THE EYE BUT IS FINITE IN DEPTH

Modern technology makes it feel like we possess infinite knowledge at our fingertips. But that’s not true.

Our online environments only appear infinite. The deepest, most nuanced knowledge still lives beyond any device. Everything we see through search, social media, or AI is limited to what has already been indexed, posted or trained. For example, Google may index hundreds of billions of web pages, yet that still accounts for <5% of the internet. The rest sits in the deep web – private information, profiles, messages and spaces locked behind passwords, paywalls and encryption – unreachable. Also consider all knowledge that’s never been coded, or cannot be coded by a machine.

So both things are true at once: the internet is both too large for any one person to fully grasp in their lifetime, and yet that internet is still nowhere close to a true reflection of all our human knowledge.

To be clear, this doesn’t mean these technological gateways aren’t extraordinary. They expand our minds in ways no past generation could ever have imagined. But reality can’t be fully understood without curiously wandering beyond a feed and paying attention to the physical world, to people, places and knowledge uncaptured by the internet.

Randonautica is a viral app with a cult-like following that launched in 2020 (h/t Ruby Justice Thelot). Users set an intention, and the app generates random nearby coordinates for them to explore in the physical world. The idea is to alter one’s reality by breaking out of their existing reality tunnel and pushing them into unexpected experiences. The app became infamous after some people stumbled into unsettling situations, including one case in Seattle where teens found human remains near a Randonautica location.

But does the app actually alter reality? Or is it that once users set an intention, enter a new environment, and tune their attention, they simply notice different patterns and assign new meaning to what was always there? Much like the gorilla and basketballs, what we notice depends on what we’re primed to see. “Touch grass” isn’t just a cute meme. It’s a reminder to break the 24/7 infinite loop and widen our aperture of attention so our field of reality expands.

07.

TO MISTAKE THE STAGE FOR THE WORLD IS BE TO CONQUERED

Even within the limited reflection of the physical world that we see online, there’s no guarantee that any of it is real. As Sun Tzu says,

“All warfare is based on deception.”

The idea that people perform for each other isn’t new. In 1956, half a century before the launch of Facebook, sociologist Erving Goffman pioneered the dramaturgical approach to viewing social life as theater. He viewed each of us as actors, playing roles on a public front stage to shape how others perceive us, and then retreating to the backstage of our private lives. In our current social media era, we’re more aware than ever that everyone is performing. Yet this awareness doesn’t seem to make us any less susceptible to staged performance, or curbs us for performing ourselves. Even authenticity is now a performance and manufactured aesthetic.

Much of the current discourse is panic about reality collapsing every time a photorealistic image generated by Nano Banana goes viral. But the challenge of discerning what’s real online has existed for far longer than debates about generative AI or the authenticity of images.

Even those who preach media literacy and cultural fluency still fall for these traps. They believe information is staged when it isn’t, like the claim that HBO engineered “the mob-wife aesthetic” trend as a psyop for the 25th anniversary of The Sopranos. They in fact did not. And they believe information is real that is actually staged, like Charli XCX joining Substack to journal about the realities of being a pop star, which in reality is a professional entertainer being paid to strategically use the aesthetics of raw confessionals as an ad for both the platform and her upcoming album.

None of this would matter if we treated the online as an entertainment stage, a series of magic tricks, a dreamworld. Charli herself acknowledges the fun in blurring the lines between truth and performance. But reality becomes strange when we continuously mistake performance for truth and pass it around as insightful cultural signal. Much of today’s commentary now looks less like real cultural analysis and more like white collar fan fiction and conspiracy theories about what’s happening “backstage.”

At the end of the day, we’re all putting on a front stage performance that’s shaping real life decisions, but many are forgetting it’s all just an act. As a result, even among people who claim to defend media literacy, we’re losing our grip on what’s real and what’s a performance.

08.

REALITY IS NOT COLLAPSING, BUT CONSTANTLY RECOMPOSING

Our shared sense of reality is always shifting. It has always gone through cycles of breaking apart and coming back together in new forms.

Venkatesh Rao argues that we don’t live in one “real world,” but in near infinite overlapping belief-worlds – different religions, fandoms, economic theories, political ideologies. The “real world” is simply the dozen or so belief-worlds that are most consequential at a given moment. Only a few meaningful stories shape history, and even those rise and fall as collective belief changes. Power, wealth, popularity, or even truth don’t guarantee that a world matters. Only consequentiality does. As Anaïs Nin said,

“We do not see the world as it is, but as we are.”

Rao gives the example of Galileo vs. the Catholic Church. In the 17th century, Galileo was right that the sun doesn’t revolve around the Earth as the center of the universe, but the Church’s constructed world was more dominant and consequential than his truth. Galileo’s true world didn’t become consequential until many centuries and technological developments later. It wasn’t until about 350 years later in 1992 that the Vatican formally acknowledged the Catholic Church’s error in condemning Galileo. Oops.

So what we call the “real world,” our shared social reality, is really just a temporary construction which lasts only as long as enough people believe in it. Reality is in constant negotiations. When belief fades, that world dissolves and a new one forms. Today, for example, we can see the neoliberal world losing consequentiality, while the worlds of Trump, mysticism and the accelerating AI arms race rise.

Understanding reality isn’t about infinitely chasing truth with our finite attention. It’s about understanding which worlds are becoming more or less consequential.

Perhaps part of why we experience reality collapse is that 24/7 media and infinite access to information allow us see more of these worlds rising, falling, and recomposing. The churn was always happening. We just couldn’t access it in real time... until now.

09.

VICTORY BELONGS TO HE WHO KNOWS LIMITED ATTENTION IS NOT A WEAKNESS BUT A STRENGTH

Sun Tzu himself wrote,

“If he sends reinforcements everywhere, he will everywhere be weak.”

Even Sun Tzu understood that finite resources must be spent wisely. The same law governs the attention war. Survival isn’t just about what you focus on. It’s about what you deliberately refuse to focus on.

Restraint is a winning strategy.

Limiting our attention is not a weakness. It’s how we maintain mental fortitude.

Move on.

10.

MASTERY BEGINS WITH TRIAGING WHAT CAN BE CONTROLLED AND WHAT IS DISTRACTION

So how does a soldier navigate the battlefield of attention?

It begins with a system of triage.

Looking at the work of psychologist Julian Rotter, we must ask, what is in our locus of control? I.e. What can I directly act on right now? What is in our locus of influence. I.e. What can I not control, but can affect over time? What is in our locus of concern? I.e. What are the things I deeply care about, but cannot meaningfully change? And what is in our zone to ignore? I.e. What is everything outside my knowledge and reach, which I must accept I don’t and can’t fully know?

In our current 24/7 culture and relationship with media, we’ve become so disembodied from our physical surroundings. In a weightless state, it’s become much harder to discern what is actually within our control or influence, our inner locus, and what’s actually materially consequential to our lives.

Instead, so many of us get stuck endlessly in the outer locus of concern – the areas far outside our control or influence – expending scarce attention on things we dislike, can’t meaningfully affect, or don’t even need to have an opinion on. We form opinions about everything, unable to have an informed opinion about anything.

Francis Bacon warned that when we have no clear “prenotion or perception of what we are seeking, we seek and toil and wander aimlessly, as if in infinite space. Whereas, if we have a particular prenotion, infinity is at once interrupted.” When our attention narrows, we can move forward with purpose.

Nietzsche, in On the Use and Abuse of History for Life, argued that active selective forgetting is essential for life itself. That without the ability to let go of the infinite, action becomes impossible. He warns that the infinite overwhelms the present and weakens vitality, and that every living being needs a limited horizon.

To be very clear, this is not about anti-technology or anti-ambition. It is pro-focus, pro-intention, and pro-discernment in how we understand broader historical contexts and apply the affordances of modern technology and media to our own ambitions. This is a call to reclaim our attention as a finite, precious resource.

11.

STRATEGIC FOCUS IS NOT STRATEGIC IGNORANCE

Now, to be clear, there is a dark side in shifting from the infinite to the finite.

We risk an overcorrection to an overcorrection. We can turn too far inward, toward isolation, narcissism, echo chambers, tribalism, xenophobia, and authoritarian nationalism. We’re already feeling these worlds gaining consequentiality today.

But strategic focus is not the same as strategic ignorance. In The Unknowers: How Strategic Ignorance Rules The World, sociologist Linsey McGoey warns about ostrich instruction, dissociating and claiming ignorance to absolve one’s self of responsibility, like the myth of an ostrich burying its head in the sand.

The flood of infinite information leaves us overwhelmed, manipulated, and exhausted. It’s a lot. Limiting what we take in defends us – but only if we retain self-awareness and humility of what we don’t know, and stay curious and humble enough to learn from perspectives outside our immediate field of view. There is much that we don’t know and can’t affect.

This is permission to find comfort in knowing that we cannot, and will not, know or change everything.

Good luck out there, soldier.

As your eyes wander from here to the next patch of digital terrain, will you march forward with intention, tighten your grip on your attention, and ask yourself, why are you here?

Now, move out and on.