Feeling Invisible Worlds: Spatial Computing, Haptics & A Future of Perception

According to Accenture, 92% of executives revealed “their organization plans to create a competitive advantage leveraging spatial computing.”

We’ve heard the term before, but like all hyped trends, are we considering all the implications of spatial computing? And further, what’s technically and socially required as we blindly accept its future?

Firstly, what are we even talking about when we say “spatial?”

Historically, we once had to go visit a designated location to use a giant computer. Then with PC’s, we constructed “the computer room” — a designated space in our homes where if you could afford one, the computer lived. Then we got the laptop. Soon every room became a computer room. With smartphones, we no longer needed rooms — the computer was untethered and traveled with us. We could watch TV, order things we didn’t need, and access all the information in the world, anywhere. Then, bypassing the pocket, wearables put the computer in direct contact with our skin. Today, we don’t even have to think about our usage. Computers are passive, always running on, and increasingly, inside of us.

Study this pattern closely and the next evolution becomes clear:

We’re moving towards a future where the computer becomes omnipresent, no longer constrained to a screen.

The computer is everywhere.

Coined in 2003 by MIT Media Lab researcher Simon Greenwold, spatial computing defines the radical blur between our physical environments and virtual, digital experiences.

The erasure of this divide is imminent.

Earlier this year Apple set the pace releasing and selling over 200K Vision Pro Headsets, arguably the largest mass market Mixed Reality (MR) device. Its adoption was suspect, but it was importantly different from other Virtual Reality (VR) devices in that the Vision Pro took in the physical world around the wearer and then overlaid virtual objects or digital media on top of it.

Conversely, VR devices do not input a physical environment and instead only display digital content via complete immersion. In VR, you only see a screen – whether that be a video game or footage from space – not what’s actually behind the goggles.

While we’re splicing hairs... Augmented Reality (AR) enhances the view of our immediate physical environment by overlaying computer images. If this sounds nearly identical to MR, fair — they’re incredibly similar and often conflated. The difference is that AR allows you to perceive your physical surroundings entirely, with digital contents only overlaid secondarily (ex. Google Glass or PokémonGo). Meanwhile Mixed Reality (like the Apple Vision Pro) blends digital and physical into a single stream. In other words, the Vision Pro uses cameras outside of the goggles to display a digital rendering back to you with virtual components mixed in. (Technically, when you use a Vision Pro to watch a movie that takes up your entire field of vision, you’ve just entered VR.)

Extended Reality (XR) is the umbrella term for all of these manifestations.

So, with...

1. The decline of hype investment in “Metaverse, VR and AR” companies,

2. Apple’s foray, investment, and continued confidence in the Vision Pro despite slowing sales velocity,

3. Tailwinds across other institutional investment and production of all types of XR (ex. Meta’s Quest, XREAL, Magic Leap, Varjo, Brilliant Labs),

4. The continued ubiquity of wearables (ex. Apple Watch) and health trackers (ex. Whoop, Oura Ring) and the emergence of a new class of AI devices (ex. Humane Pin, rabbit r1), and

5. Progress around the chips and screens required to usher lighter wearables...

Spatial computing has more going for it than against it.

As former Microsoft Strategist, bullish tech evangelist, and author, Robert Scoble puts it,

“When this technology becomes more of a glasses form factor, it’s going to light a fire. Everyone on a New York City Subway train is going to be wearing them. I can see glasses happening in three years, maybe five. It’s really hard to see it being longer than five years from now because I’ve seen some of the other products coming, and there is real competition coming.”

Unlike other hyped “sci-fi tech,” spatial feels different as there’s undeniable progress to extrapolate from. It only makes sense that omnipresent computing comes next.

With spatial computing’s hype validated, we can finally touch upon perhaps the most fascinating and under-discussed requirement of this future: haptic technology.

Haptic tech is often thought of as “the rumble” from hardware devices. It’s not new. You may have had a Rumble Pak for your Nintendo 64 in the late 90s, which would vibrate your controller, augmenting the gaming experience.

Nearly 25 years later, we take these haptics for granted. Our phones don’t even have to make a noise, and without looking, we know if we have a text or call. How? Vibrations. Haptics.

Haptics are critical to our digital experiences as these gentle, physical sensations travel to our brains significantly faster than both visual and auditory cues do.

For Biomedical Engineer, Dustin Tyler,

“Touch is actually about connection, connection to the world, it's about connection to others and it's a connection to yourself, right?

We never experience not having touch. It's the largest sensory organ on our body.”

Haptics or “touch” is a prerequisite for an effective interaction.

We’ve come a long way since Apple’s 1983 Lisa computer, which was the first commercial computer with a graphical user interface and a mouse. This mouse would allow its users to gain visual confirmation, but also tactile confirmation: CLICK.

Apple continues this tradition with haptics. Unlock your phone, text or use Apple Pay, and you’ll receive pleasant, minor vibrations affirming — physically nonexistent — digital actions.

Haptics bridge the gap between the physical and digital.

But historically, these critical confirmations emanated from a device in our hands.

So the question becomes...

With a continued physical-digital blur and a world where everything becomes overlayed with digital content – likely coming from something worn over our eyes – where may our critical tactile information come from?

Afference is one company attempting to answer this question.

As CEO Jacob Segil explains,

“We’ve gotten 80% there with visuals and audio. We’ve predominately spent the last handful of decades focused on and innovating around screens and cameras — the visual. It’s been a real arms race. But with the future of spatial, we’re interested in that 20% and want to close the loop. How? Haptics.

We completely underestimate the value of haptic feedback.”

But the way in which Afference is going about haptics is quite unique. After all, try out the Vision Pro and there’s nothing in your hands. No Rumble Paks or haptics engines are producing assuring vibrations.

Today, you have no physical confirmations.

Afference is using neuroscience to develop the mere sensation of haptics. But they’re not entirely “real” — much like the overlaid graphics atop of our displayed environment. The haptics are illusions. Neural stimulations of artificial touch. No blade or surgery required.

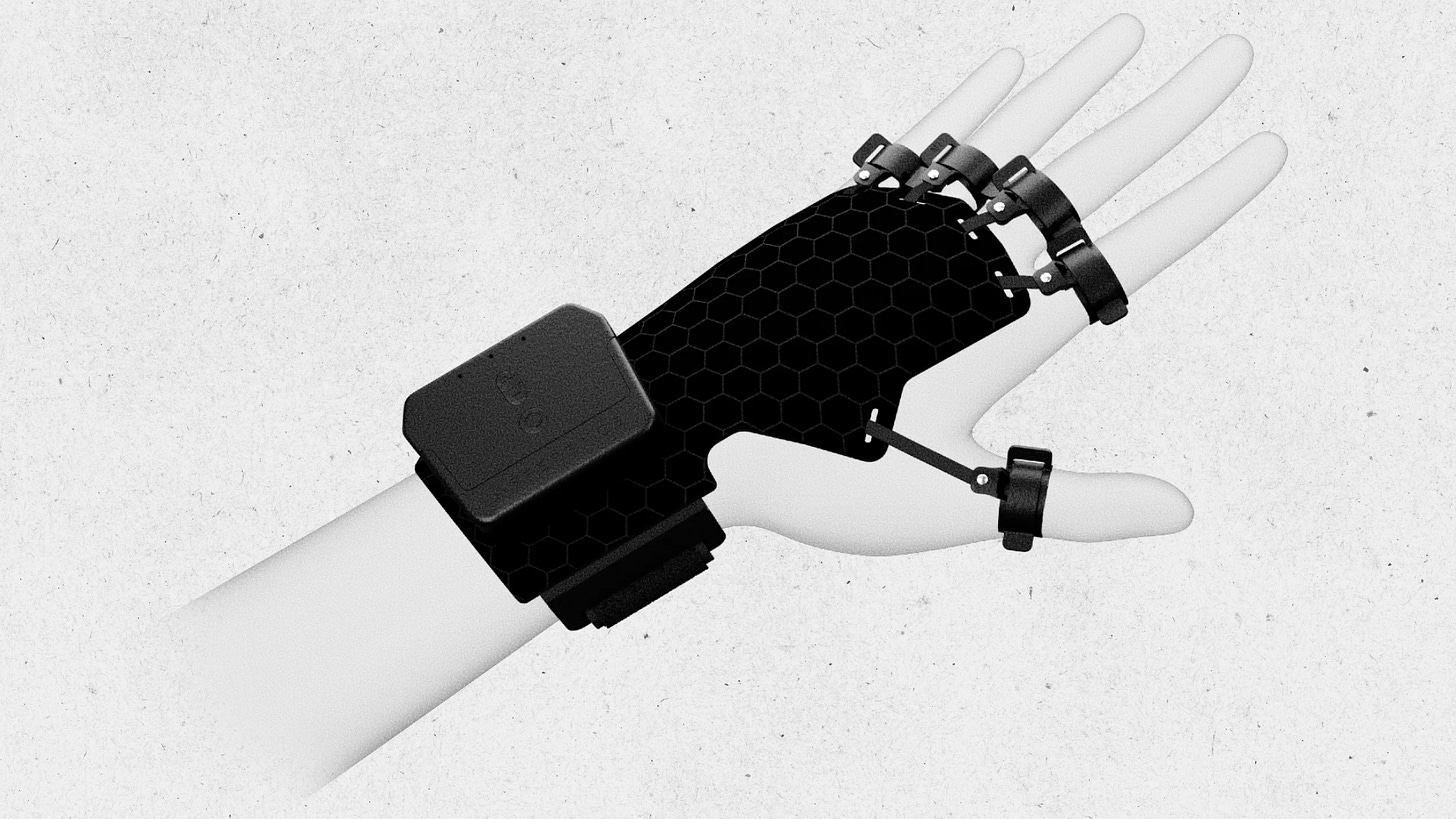

Their current “glove,” called the Phantom, uses electronics to provide radically precise stimulations, producing the sensation of touch in your fingers.

“Your brain feels sensation when electrical signals are received from your skin. We ‘hack’ the wires connecting your skin to your brain and add new information. Then, the brain feels things that aren't there.”

If we’re to increasingly rely upon tech and blur the physical and virtual, we must ensure physical feedback is in the loop. The alternative is just attempting to interact with air.

Segil continues,

“If we’re going to be using our hands [in this spatial computing future], we’re not feeling anything. There’s no confirmation or feedback.

Life is too slow and cumbersome without the tactile. It puts a cap on our experiences.”

Our lives are multi-sensory. And it only makes sense that our digital experiences become so as well.

But to expect we’ll soon be able to feel cotton that isn’t there... well, that's where things get unrealistic. There are 17,000 receptions in the palm of our hand. There were only 15 channels in Afference’s early prototype.

“Fifteen to 17,000. We’re not going to solve this problem overnight. But we’re not going for natural. We’re going for useful. We’re calling it ‘Digital Dexterity.’

Essentially, a better way to consume, interact and enhance – not disrupt.”

As Luke Robert Mason, a futures theorist who studies tech developments and what it means to be human, puts it,

“‘Sensory Substitution’ is a rich field of research, which explores ways to bypass one traditional sensory organ by using another.

It reveals the ability of our brains to have a profound relationship with technology and proves how important touch is in our experiencing the world.

Devices like Afference will have real function in not the replication of the senses but their substitution.”

Luke continues,

“Haptics promise a future in which we can feel virtual space, but these sorts of devices ask an important question about how virtual much of our lived experience already is.”

The emerging implications around haptics are endless:

If we’re already struggling to distinguish real vs. fake, what happens when tactile experiences only enhance virtual experiences, increasing their perceived value or influence?

Augmenting Empathy

What happens to intimacy and affection? Virtual handshakes, hugs, or even pats on the back can soon be felt and even commonplace, potentially leading to increased empathy. But what about the non-consensual pat on the rear end...

Consenting Touch

Ethical questions arise with the ability to simulate physical sensations virtually. Consent and exploitation. British police recently launched the first investigation into “virtual rape.” What happens when such experiences and traumas are only exacerbated by unwanted physical sensations?

Disintegrated (Legal) Boundaries

Further, what are the legal and regulatory questions we should begin to consider? How may property rights, privacy laws or anti-discrimination policies evolve as our physical and virtual realms blur, and does touch become available to all around the world?

Accessibility

Coincidentally, this tech was funded for veterans with amputations, paralyzed or unable to sense touch. But not only do mass market accessibility questions remain unanswered – how does future haptic tech work for not just all bodies, but all minds too, like those on the autism spectrum who can experience hypersensitivity or hyposensitivity to sensory input. Then there’s also the financial accessibility element. How can this tech be affordable for all, preventing experiential inequality?

And perhaps the most noteworthy and dire implication...

Screen(-less) Time

Afference is seeking to build a “heads up” vs. “heads down world.” In other words, a world where humans have their eyes up at one another, rather than down in our devices, stealing attention. Spatial computing only intensifies this tension.

When we look back on the loss of the computer room, screen-time dramatically increased.

On one hand we have the screen-time tech lash, dumb phone love, digital sabbaths, and global platform lawsuits. Yet on the other, a natural progression of innovation, adoption and reliance upon tech.

We’re ushering in a world without a physical-digital divide in a moment when we’re so seemingly upset with it.

What happens when our reality is viewed through glasses constantly, layering digital content everywhere?

“Screen-time” becomes meaningless.

All of life becomes mediated through a computer.

What ails us from smartphones today only gets more aggressive when we forecast a future of spatial computing.

That we’re already dramatically struggling with our digital hygiene paints a grim signal of what happens next: We’ll soon bathe in the virtual. Computing will no longer be regulated by a tiny screen, room or pocket, but become virtually omnipresent. And the virtual will be affirmed by touch, only exacerbating its power.

We debate what’s “real” or not. But images are just the beginning. The dividing line of reality is dissolving.

The growing ability to comingle physical environments with synthetic, simulated layers challenges one of the most foundational aspects of the human experience – shared perceptual certainty.

When our bodies can be manipulated into feeling forces that do not objectively exist, the foundations of our senses crack. Reality itself becomes a malleable, cognitive “Choose Your Own Adventure.”

Perhaps most needed, we must kindle a spirit of epistemic humility and brave vulnerability. By maintaining an openness to new ways of seeing, feeling and simply perceiving, we create space to navigate the unprecedented and script what happens next.

It’s not spatial computing itself that will forge the future, but rather the consciousness we bring to how we inhabit it.

And if we’re to trust Accenture’s findings, nearly all surveyed executives are already building this future, whether they know what it means or not. Or further, whether we’re ready or not.

This report was written in collaboration with Hannah Grey VC, a thesis led venture capital firm, where I reside as their Resident Futurist. Afference is a Hannah Grey portfolio company.

This report is a part of a series of analyses forecasting future markets. Our previous collaborations studied the cultural implications of pandemic learning loss and Ozempic and other longevity drugs.