"Out of Office" Meme Report TL;DR + Q&A with Jennifer Chang & Anastasia Kārkliņa

Out of Office: An Investigation of Memes, Meaning, and Linguistic Competence Online and IRL is a new report from Jennifer Chang (JC) and Anastasia Kārkliņa (AK), two brilliant cultural analysts, who explore the origins and futures of online meme culture. Covering:

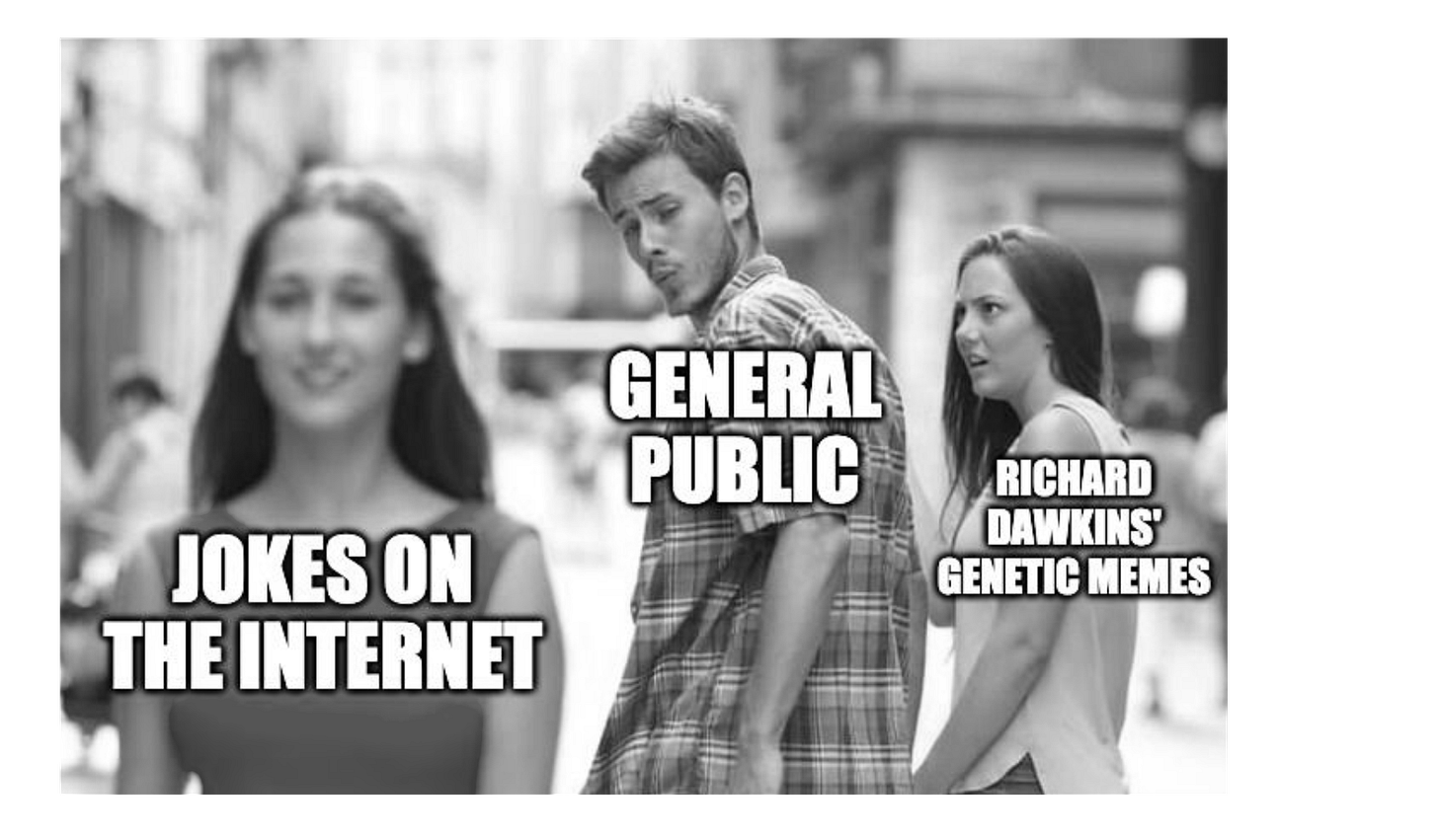

Dawkins’ Memetics, Godwin’s Law, Speech Acts, Virality & Social Contagion, Language Development, Gen Z’s Visual Language, Remixing & Ownership, Meme’s Culture Role, IRL Memes, Brand Co-opts, Social Movements, Dangerous Memes, Digital Blackface, Mental Health, NFTs and Future Folklore

This report is by far the most comprehensive yet approachable take on the subject. I may be biased.

While I had the honor of helping shape the work, I also spoke with Jennifer and Anastasia about their personal findings. Edited for clarity, below, please find our conversation and snippets of the report itself.

Memes are cultural and linguistic media that serve as a kind of shorthand for taste, style, or personality.

Memes are frameworks; they’re skeletons.

Functionally, they are images that are remixed and circulated, but in essence they are a shortcut to social acceptance: a shared language of relatability, and a surface-level way of signaling something about yourself and your interests to facilitate relating to other people, without divulging too much personal information.

MK: Memes are on the top of everyone’s mind today, from Stonks to Sea Shanties — but it feels as if these low-brow memes never get the high-brow treatment. Why a full-blown report?

JC: I thought there was a lack of discussion around the broader significance of memes beyond anecdotal evidence or individual memes. We wanted to explore what memes actually mean from a linguistic and cultural perspective — what they represent in terms of communication for humans and how they’ve become this entire language that takes a lot of cultural fluency to understand.

Like linguistic idioms, memes are not only a way of participating in culture, but also an intentional way of communicating a recognizable level of cultural intimacy.

With the right amount of traction, memes can become part of our everyday lexicon—a cultural currency to be exchanged for social recognition.

AK: The deck exposes the complexity of what seems ordinary; that is, quotidian parts of culture that we encounter and actively engage with but often take for granted. What happens when we pay close attention to what we might first see as “just a GIF”? We uncover histories, genealogies, and ideologies that can tell us something really important about how we live, communicate, and behave.

Humor, trends, and memes are reflections of both current anxieties and cultural idiosyncrasies, but they also help shape and are shaped by media—if you control the media, you control the culture. Ultimately, memes ‘speak rich collective truths that resonate with people.

For Gen Z, everything is content and all content communicates.

For a generation which holds such complex, nuanced sentiment, these nonverbal but colorful mediums are required to get across what’s felt.

MK: The value of this critical deep dive allows you to give weight to the overlooked or superficial features of today’s memes. What was most surprising thing you came across in your research?

JC: I was amazed by the relevance of old concepts, like Marshall McLuhan’s “global village” and Richard Dawkins’ original definition of the word “meme.” These theories are decades old, and yet in retrospect they were incredibly — often eerily — prescient, and now they’re being applied in ways that the original creators never would have dreamed of. More broadly, I’m always fascinated by intersectional and systemic thinking. As we gain a more nuanced, intersectional perspective of the world and learn to think critically, it’s truly incredible to really untangle all of the little things — even seemingly insignificant ones — that explain who we are and why we behave the way we do.

Memes “contain an informational element of instruction or rule for doing things... which can [also] spread like a virus,” and so we can understand viral internet phenomena like memes as instances of “social contagion,” meaning that sociocultural occurrences spread amongst populations more like accidental diseases rather than rational choices.

Ultimately, memes are a reflection of our desire for social influence and conformity (especially among teens), and our propensity for imitating those around us.

AK: For me, it was Legacy Russell’s forthcoming book BLACK MEME, in which she argues that the images of Black death and suffering, e.g. lynching photography, were early examples of mimetic material in the United States.

Memes have blurred the line between media consumption and production. Users aren’t just passively consuming media anymore—they’re critiquing, remixing, and broadcasting it in real time.

MK: The pattern here is we often think of memes as new or fringy features of our “very online” culture, but they’re truly as old as time. After all language, fashion and religions are by definition memes. And by viewing them that way, we can recognize how vital they really are. What else do you think people get wrong about memes?

JC: People still think they're really frivolous and they don't really mean anything. But the deeper you look, the more you realize that there’s always a reason behind the reason. A trend might appear silly or meaningless at first, but there’s a reason people feel compelled to participate and a reason it catches fire. I think memes also highlight how arbitrary our world is. Everything — money, power — is only worth however much we decide it is, and that’s often contingent upon what other people think it’s worth (i.e. mimetic desire).

Memes can be a legitimate form of protest, a way of conveying opinions or dissent when free expression is discouraged or dangerous, or symbols with political meaning. Like the Umbrella Movement in Hong Kong or the 🍚🐰 emojis being used to evade censorship of the #MeToo movement in China, internet culture often intersects with activism.

AK: Memes are forms of communication that are always already implicated in relations of (racial) power. I’d encourage readers to look further into existing research on the digital blackface, some of which we have highlighted in the deck. How and why we use memes is not at all politically neutral nor divorced from our social realities.

Pop culture has always influenced politics, but the two are inextricable now that so much of political discourse takes place online.

Our “global village” and the social knowledge it contains is perpetually developing, and especially in the pandemic we are finding ways of connecting with one another that we never thought possible, which includes using memes to engage with events that scale from personal to global.

Memes are no longer simply artifacts of culture but culture themselves, a language as rich and diverse as we are.

After all, we made the internet and the internet made us.