Future Burnout: On the False Promises & Expectations of What Comes "Next"

The following piece is a collaboration between Matt Klein + Akili Moree.

Akili Moree is a cultural theorist and strategist, analyzing how technology shapes culture, and exploring its impact on identity, community, and social change. At 22, he brings a fresh perspective to understanding our digital landscape. He recently founded RODEO, an advisory firm that provides brand strategy and cultural insights to companies looking to connect with youth. You can find him on TikTok as @akili3000.

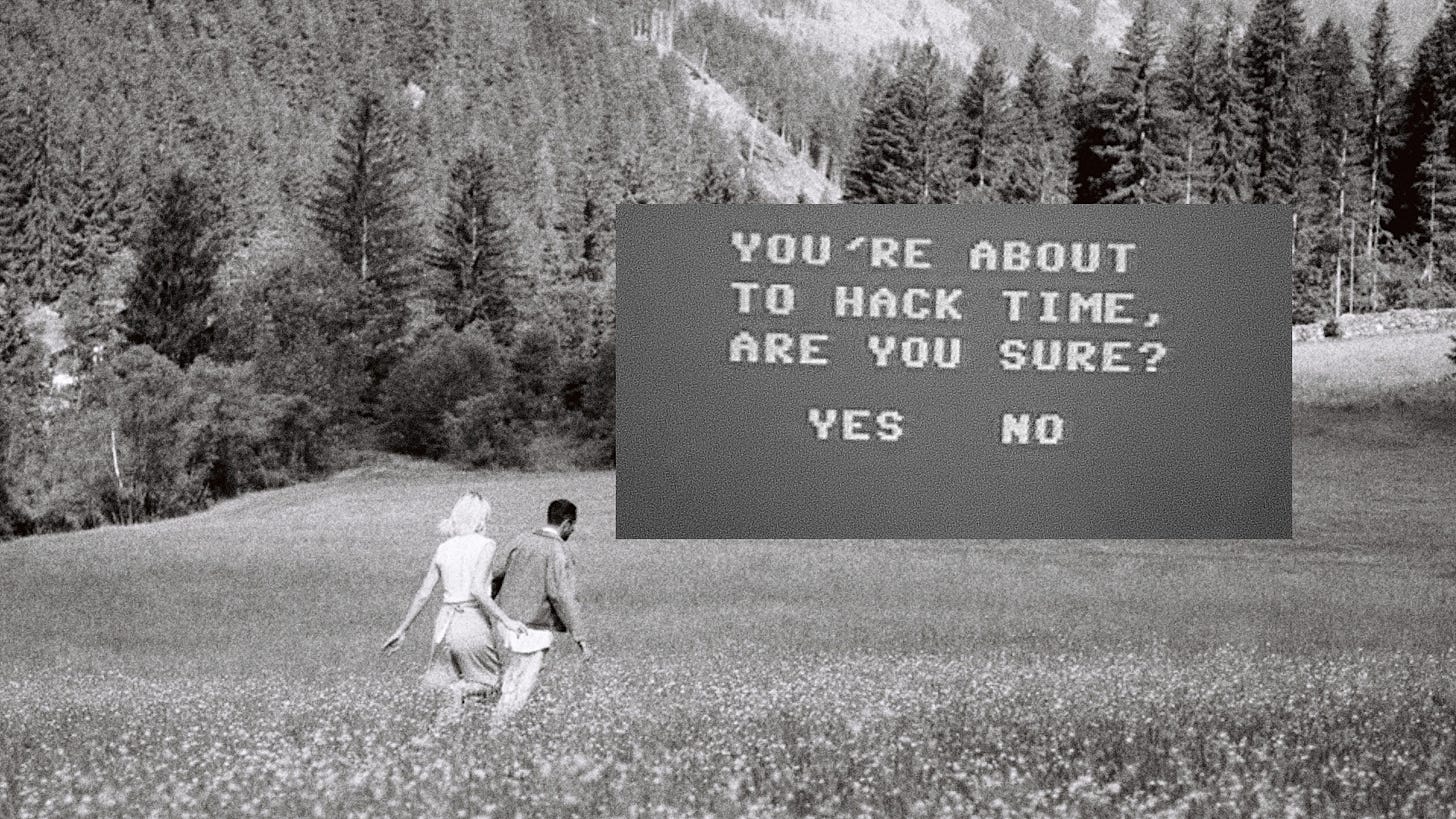

One of the central anxieties that has permeated culture for the past decade has been a temporal one.

We've been living in an argument between the future and the past – a tug-of-war between the glistening promise of what's to come and the comforting nostalgic pull of what once was. It’s also a battle between the dread which looms and the dark past which haunts.

This tension of future vs. past plays out in countless ways, both big and small. It's in the breathless hype surrounding each new technological breakthrough, contrasted with the wistful longing for simpler times and reboot mania. It's in the constant, energetic churn of social content, where each moment is viewed as a performance to be documented and dissected in the future, set against the backdrop of a yearning for a more conventional, authentic, and analog existence.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to ZINE to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.